By Samuel R. Mendez. July 20, 2023.

Artists have a lot to teach public health professionals. This includes how to build an audience and create memorable experiences. More importantly, artists can also teach us to transform ourselves and, in turn, the world around us. If we want to achieve health equity, this type of transformation must be part of public health.

In spring 2020, I was finishing my master’s degree online. Those couple months marked more time in person than my partner and I had spent together in several years as a couple, thanks to school, work, and life itself.

The surrealness of that time still sticks with me. An afternoon spent waiting in line for the grocery store. A graduation in the kitchen. A birthday on screen. We all were there.

Thanks to the magic of recommendation algorithms, I heard a song for the first time. Browsing the YouTube comments revealed a shared experience. “When my kids ask how quarantine was I’ll explain with this song.”

“June Gloom” is a song describing Allie X’s experience growing up with an autoimmune condition, an increasingly common experience in the US. It comes from Cape God, an album inspired by a documentary about the opioid crisis in Massachusetts, where over 2,000 people have died from opioid overdose each year since 2016. Allie X has described the common ground she found with people featured in the documentary.

“They don’t know if they’re going to survive. They had problems connecting to their family. They have so much shame. There was just all these sort of parallels.”

By sharing these emotional insights, she built an audience able to feel a sense of commonality around addiction, chronic illness, and pandemic-era isolation. Fans may not learn facts and figures, but isn’t this emotional insight also a kind of education?

Stigma is a barrier to opioid use disorder treatment, a factor related to lower quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients, and a common experience around COVID-19 in the US. Stigma is a powerful force based on emotion more than fact. So why shouldn’t emotional insight be part of a public health strategy to address it?

There are many formal ways to understand the power of art. Literature scholar Doris Sommer explained public art’s power via its ability to create freeing experiences outside of everyday political and economic constraints. Social epidemiologist and poet Ryan J. Petteway described poetry as a powerful form of critique, self-empowerment, and knowledge production in the face of racism.

When public health communication includes art, however, it doesn’t typically focus on imagination, freedom, or power. It tends to focus on information. Researchers have used telenovelas to teach people about genomics. Narrative games have proven useful in changing health behaviors, as have audio-visual narratives. Beyond the scope of health communication, the arts are gaining prominence as a public resource that can promote individuals’ health outcomes. While this utilitarian approach has led to positive outcomes, it still doesn’t reflect art’s potential to disrupt and transform.

“Way Back” by Amber Mark comes at the end of 3:33am, an album about the grief she felt around her mom’s death from cancer. I first heard it around the time a good friend was dying from cancer. Over time, my relationship to it changed as I processed my grief. At first it felt like a peek into the future: if she found a way out of the thick of grief, I would too. Then it felt like a way to describe the ebbs and flows of healing. Its blurring of past and present resonated with my own attempts to make sense of my growing distance from my friend and our relationship from our early twenties.

Eventually, the song became an inspiration to be more open with my feelings of grief and anger more broadly.

“Turbulence” was a drama therapy production by NYU’s Theatre and Health Lab. It actively engaged audience members in exploring BIPOC experiences in clinical settings. In reflecting on her experience of co-creation, music therapist Jasmine Edwards described how the space of the partnership helped her process her own racialized experiences and connect with others over theirs. In her words, she was, “seen, heard, understood, and, above all else, held.”

The COSECHA study is a youth participatory action research project that looked at Latina teens’ exposure to pesticides in Salinas Valley, California. This led to research findings on the geographic distribution of pesticide exposure, as well as a community mural. Partnering artist José G. Ortiz describes the importance of this artistic approach, thanks to its ability to “communicate a feeling, a thought, a dream, an idea. And how we process that can make it come to life.” This aligns with the broader work of his arts organization Hijos del Sol. He describes the space they’ve made as, “a place, a home, where we can practice at an early age who we truly are.”

These examples help me imagine a different kind of public health. One that doesn’t just give people information, but also creates spaces where communities can come together to produce knowledge and practice living in a better future.

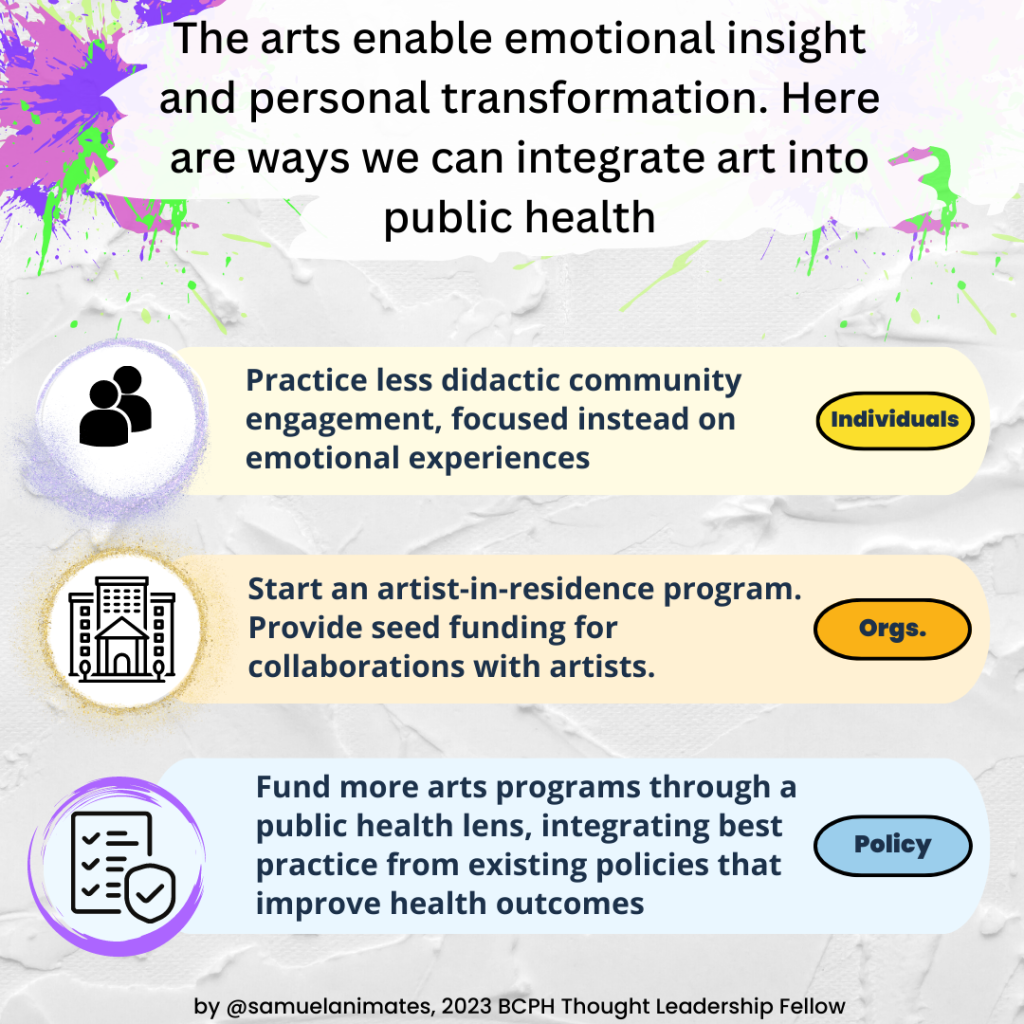

There are steps we can take to integrate the arts into our public health communication, fostering emotional insight and transformation:

You can find Samuel talking about health communication, health equity, and video games: @samuelanimates on Twitter, Twitch, YouTube, Tiktok, and on the scicomm.xyz Mastodon server.

The mission of the Boston Congress of Public Health Thought Leadership for Public Health Fellowship (BCPH Fellowship) seeks to:

It is guided by an overall vision to provide a platform, training, and support network for the next generation of public health thought leaders and public scholars to explore and grow their voice.