Health is defined by the World Health Organization as the “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1

In a “post-COVID” era – if one can even call this time in life that – health is on the radar of the public more than ever before. We know diseases like the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) can have debilitating impacts on individual’s physical2 and mental health,3 that they can be life-threating to some populations while mildly inconvenient to others,4 and that interventions designed to prevent and treat illness rarely follow a one-size-fits-all approach.5

The right to health is globally recognized as a fundamental right available to all human beings and an obligation of governments to their constituents.6

Why, then, do public health and global health efforts around the world continue to fail?

Why aren’t countries on track to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being at all ages (SDG 3) or achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (SDG 5), goals all countries agreed to by 2030?7

Because key communities continue to be left behind.

Nearly half of the world’s population are women and girls, yet gender equality has yet to be achieved.8 Women and girls have some of the poorest health indicators around the world. For example, child marriage (union before age 18) affects women and girls over five and a half times more than men and boys; 650 million women and girls alive today entered a child marriage compared to 115 million men and boys.9

Every day, 800 women die in pregnancy and childbirth; most of these deaths are completely preventable.10 And while these statistics are especially concerning in low- and middle-income countries, where most of these cases occur,11 stories like tennis star Serena Williams’ near-death experience in childbirth remind us that high-income countries like the United States are not exempt.12

More concerning is that these indicators are often not driven alone by sex – one’s biological designation as male, female, or intersex – but rather by inequity and inequality connected to gender. Gender is the social and cultural meaning used to designate individuals as women/girls, men/boys, or other genders. It has been defined as a “social system that defines men and women as different and distributes power, resources, and status on the basis of that difference.”13 This system, which enshrines values of how groups of individuals in a society are treated based on their gender, can lead to differential health outcomes through gendered differences in health determinants, health behaviors, access to care, and what is known about health solutions.14

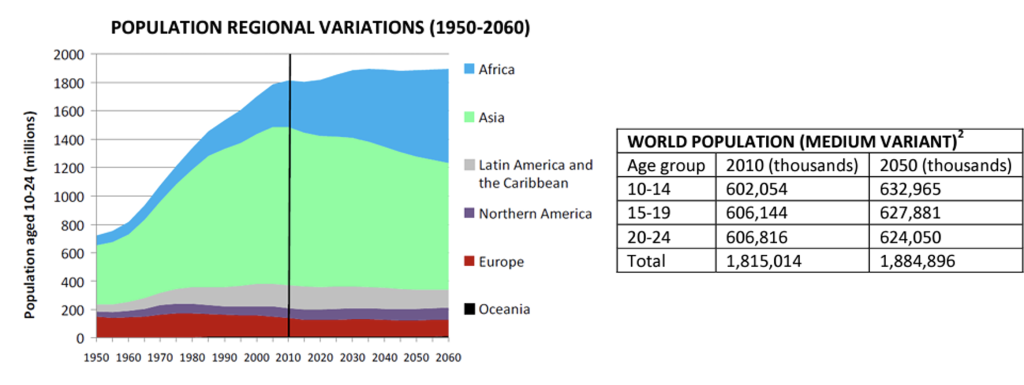

Did you know that there are 1.8 billion adolescents (ages 10-19) and youth (ages 15-24) worldwide? Adolescence is a unique period in life, characterized by distinct biological and developmental growth at this stage of life.15 More recently, 20-24-year-olds are being considered in an expanded definition of the adolescent period due to societal shifts in the transition into adulthood.16,17

Although adolescents are often considered one of the healthiest populations by age, investments in the health and well-being of adolescents can offer a triple dividend – the ability to increase returns on health to the adolescent at present, in their future adult life, and for their future children.18 That means that improving the health of young people not only will impact their present health; it also can positively impact future population health across multiple generations. Intervening during the adolescent and youth period provides a second critical window of opportunity to positively impact development.19 There’s an opportunity to co-create with and channel the power of young people, who are leaders and are poised to be the next generation of leaders, in creating solutions to the issues their communities face.

There are other social determinants of health that are critical to understanding communities left behind. I’ve previously written about the importance of understanding racism in public health and the role of leaders in overcoming these structural barriers,20 and there is powerful ongoing research to better understand this. Economic stability, access to quality education, access to quality healthcare, neighborhoods, and social and community context are the key categories of social determinants of health.21 At the root of the two I’ve highlighted – gender and age – is the notion of intersectionality, the concept that an individual’s different identities (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, political identity, ablebodiness, size, etc.) can intersect and lead to further disadvantage or discrimination in a system of power and privilege.

Over the past 20 years, in my own work on global health and gender equality, I’ve witnessed and heard stories from women and girls across sub-Saharan Africa. I’ve volunteered to address the struggles of children orphaned from the AIDS epidemic in Windhoek, Namibia; evaluated the challenges of accessing necessary social services due to experiences with gender-based violence in Eldoret, Nairobi, and Mombasa, Kenya22; and observed the experiences of women and girls who married before their 18th birthdays in urban Conakry, Guinea.23 Sometimes, there’s an opportunity to ethically share the stories of those who are experiencing these realities. Sometimes there’s an opportunity to learn lessons from those who have dedicated their careers and their lives to addressing them.

Because through those stories and subsequent lessons, as well as interrogating our own experiences of leadership in these spaces, we can learn about opportunities to challenge the status quo and truly move with communities forward.

The mission of the Boston Congress of Public Health Thought Leadership for Public Health Fellowship (BCPH Fellowship) seeks to:

It is guided by an overall vision to provide a platform, training, and support network for the next generation of public health thought leaders and public scholars to explore and grow their voice.