It takes just five minutes for the brain to die. Astonishingly, Derek Chauvin pressed his knee unrelentingly into George Floyd’s neck for a harrowing nine and a half minutes— an act that forever altered our collective consciousness. This pivotal moment sparked a global reawakening, reigniting the flames of anti-racism efforts. It’s also a stark metaphor for the suffocating grip society has imposed on the brain health of marginalized communities. Disturbingly, research exposes a glaring truth: Black patients face systemic barriers to accessing vital neurological and mental health services, resulting in worse outcomes across a dizzying array of brain-related conditions.

As a Black Physician, Neuroscientist, and Social Justice Advocate, I am acutely aware of the precarious position I hold in society, painfully aware of the grave disparities and worse brain health outcomes that disproportionately affect individuals that look like me, but also fueled by the belief that I have the power to help change them.

In this blog, I aim to shine a light on the insidious ways in which anti-Black racism has plagued the fields of neurology and psychiatry in the past and the many ways that it continues to do so today.

I firmly believe that the healthcare community bears a profound obligation to confront racism head-on. It necessitates bold action, not just on a systemic level, but within each individual. Only by dismantling the entrenched biases and prejudices can we pave the way for a future where equity and justice prevail in the realms of neurology and mental health.

But first we must comprehend the intricacies of these biases—what they are, how they manifest, and where they stem from. Let’s begin.

The George Floyd incident is an agonizing representation of how racism impacts brain health, but it is far from an isolated one. A brief dive into the annals of history, reveals the magnitude of this issue. In the 1850s, physician and psychologist Samuel Cartwright introduced the term “drapetomania,” pathologizing slaves who dared to seek freedom. Cartwright further perpetuated racism by concocting “Dysaesthesia aethiopica,” a fictitious mental illness fabricated to explain the perceived laziness among slaves. These abhorrent beliefs found fertile ground in scientific principles that supported the notion of Black inferiority. Phrenology, championed by Franz Gall and Charles Caldwell, emerged as yet another tool employed to justify the fallacious notion of Black intellectual inferiority. Phrenology proposed that the shape of one’s skull could reveal their mental aptitude, leading to the erroneous conclusion that Africans required white masters to navigate life.

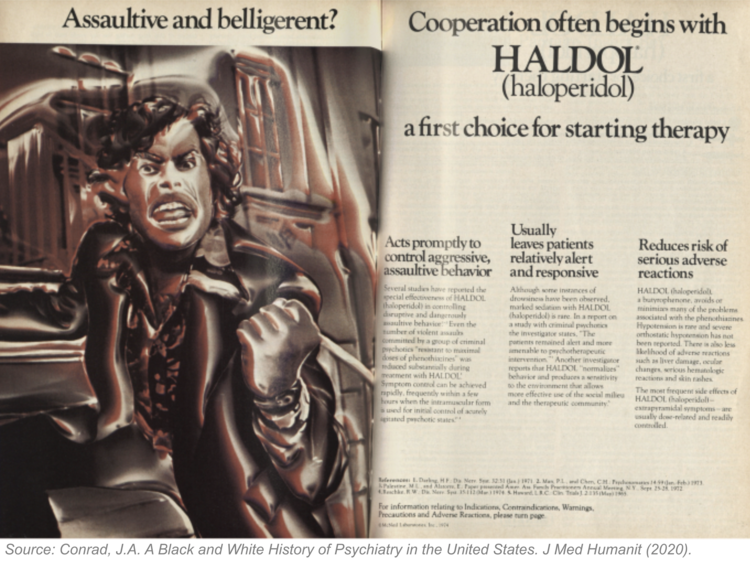

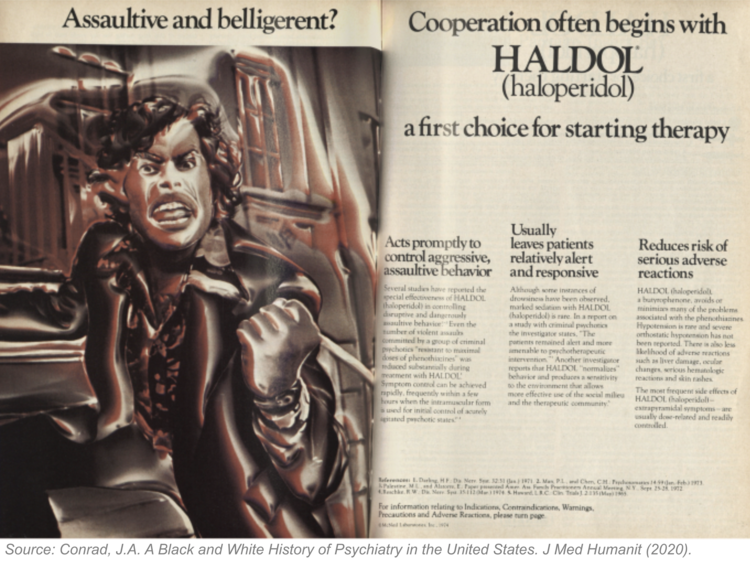

The insidious impact of these historical beliefs continues to reverberate throughout contemporary neurology and mental health diagnoses. In the 1960s, schizophrenia, once perceived as a benign affliction affecting primarily white middle-class women, underwent a grotesque metamorphosis. African American protesters found themselves disproportionately labeled with schizophrenia under the derogatory designation of “Protest Psychoses,” attributing their participation in civil rights movements as a contributing factor to aggressive and volatile symptoms. Alas, even pharmaceutical companies were complicit in perpetuating these abhorrent stereotypes. An advertisement for Haldol, a schizophrenia treatment, featured an angry Black man with clenched fists, accompanied by the words “Assaultive” and “Belligerent.”

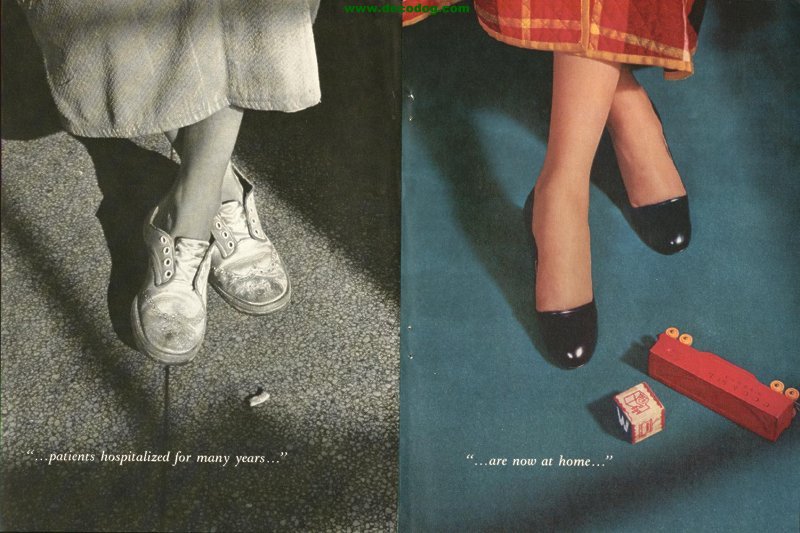

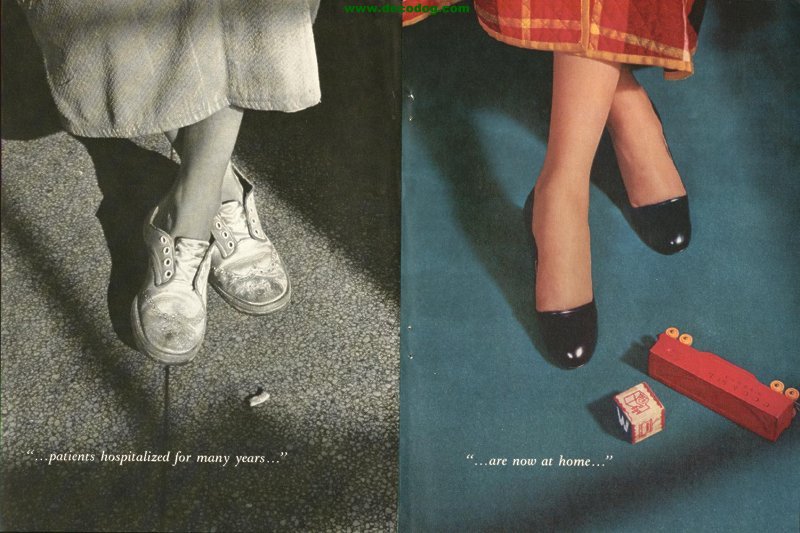

This was in sharp contrast to previous advertisements for Thorazine, another schizophrenia treatment, depicting middle-class white women as docile, and non-threatening. Such disturbing patterns persist within the realm of mental health. The term “excited delirium,” encompassing symptoms such as bizarre and aggressive behavior, paranoia, and violence, has been deployed to explain the deaths of individuals in police custody, disproportionately affecting Black men.

Likewise, the tendrils of these dangerous beliefs extend into various neurological domains today. A landmark lawsuit, brought forth by a group of NFL players, exposed the practice of “race-norming” in dementia tests, grounded in the fallacious assumption that Black individuals start off with lower cognitive function compared to whites and other groups. This discriminatory approach hindered Black NFL players’ ability to qualify for concussion payouts. Furthermore, misconceptions surrounding pain tolerance in Black patients demonstrate the destructive influence of race-based thinking, eroding the very foundations of patient care. Shockingly, a notorious 2016 study revealed that 40% of first- and second-year medical students endorsed the false belief that “Black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s skin and has fewer nerve endings,” leading to the dangerously misguided notion that Black individuals experience reduced sensitivity to pain.

Consider the differences in Figures 2 and 3.

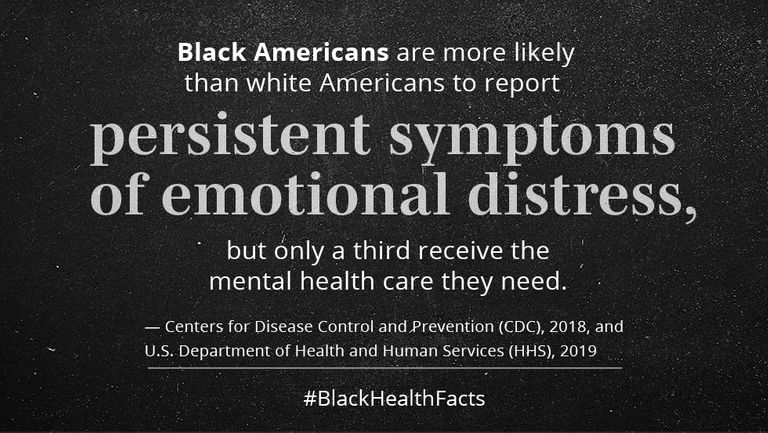

Where do we stand today amidst this sea of inequities? An abundance of evidence illuminates the numerous disparities confronting Black patients across a spectrum of neurological and psychiatric conditions:

These distressing disparities lay bare the urgent imperative to undertake targeted efforts aimed at rectifying healthcare inequities and ameliorating outcomes for Black patients in the domains of neurology and mental health.

In the realm of brain health, “Time is brain!”. Just a few minutes devoid of oxygen can spell irreversible consequences for the brain. This urgency also extends to addressing the glaring disparities in brain health, as every minute that ticks by poses a threat to permanently damage the well-being of our most vulnerable and valuable communities.

So, what can we do in the face of such pressing challenges? In this post, we began by highlighting the first tool at our disposal: awareness. It is through awareness that we can shine a light on the deep-rooted inequities and biases that permeate our systems. But this is just the beginning.

In the upcoming blog posts, we will delve even deeper into this question, exploring the array of tools available to us as we strive to dismantle this unjust system. We will explore and analyze these tools, dissecting their potential for creating a better future—one where equity and justice reign supreme in the realms of neurology and mental health.

The mission of the Boston Congress of Public Health Thought Leadership for Public Health Fellowship (BCPH Fellowship) seeks to:

It is guided by an overall vision to provide a platform, training, and support network for the next generation of public health thought leaders and public scholars to explore and grow their voice.