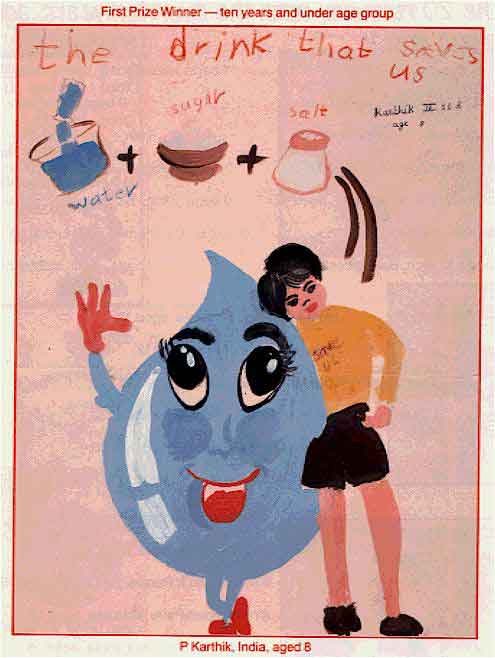

Salt, sugar and water. That’s all it could take to save a life. This combination, known as Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS)*, has been hailed by The Lancet as the most important medical advance of the 20th century.1 Between 1982 and 2007, it averted roughly 50 million deaths due to diarrhea among children younger than five.2 While ORS does not cure or stop diarrhea, it replenishes lost fluids and salts, thereby preventing life-threatening dehydration.3

The treatment’s history is equally fascinating. While it had been used since the 1940s,4 Dr Dilip Mahalanabis was the first to deploy it at a large scale in field settings.5 During the Bangladesh war of 1971, 6,000 people were arriving in refugee camps every day, leading to overcrowding and cholera.2 Without adequate intravenous saline solution or staff to administer it, Dr Mahalanabis and his team handed out ORS. The results were instantaneous and remarkable: mortality dropped from 30% to 1% in eight weeks.

Despite ORS being lauded as a “magic bullet,”6 less than half of children with diarrhea received the treatment in 2022.7 By augmenting its use, we could potentially save an additional half a million lives a year.8

A systematic review of studies from 23 countries between 1981 and 2020 has analyzed the barriers and facilitators to ORS use.9 Availability, accessibility, and awareness have been major barriers, but over time, many countries have made great strides in these respects.10 But even where ORS access and awareness are not challenges, ORS use can remain subpar. A recent Science study found that it remains underprescribed.11 The reason? Despite being aware of its life-saving potential, healthcare providers assumed that people did not want ORS. This assumption is unfounded because in the household surveys the study authors conducted, people reported it as their most preferred treatment.

Even among patients who showed a picture of ORS on their phones and said they had received a prescription for it earlier,12 doctors prescribed the treatment only 55% of the time.11 Among those who did not state a preference, 28% received the treatment.

Considering that Indian doctors sometimes prescribe expensive medicines, often at the behest of pharmaceutical companies,12 the study’s authors examined the role of financial incentives in the underprescription of ORS. They also hypothesized that stock-outs could play a role. However, based on their results and the prevalence of these barriers, they estimated that financial incentives and stock-outs explain only 5% and 6% of underprescribing respectively, while provider misperceptions account for 42%.

The study’s authors identified the following reasons for the healthcare providers’ assumptions regarding ORS:13

I imagine these misperceptions would only be compounded by the larger issues surrounding doctor-patient relationships. In India, for instance, one in four people face discrimination while accessing health services due to their caste and religion.14 Underprivileged and low-income patients often face neglect and dehumanization.15

The Science study was conducted in the Indian states of Bihar and Karnataka, which are diametrically opposed. Bihar is one of India’s poorest states16 and lags on economic and social indicators, while Karnataka, about 1,000 miles away, has a higher per capita income, education levels, and ORS use. However, the findings would probably hold true in many parts of India and the world, for reasons I shall discuss below.

One could say that ORS is a victim of its simplicity. This has been true of the treatment since its inception (see image below), an aspect that is often overlooked in conversations around its use.

In some ways, ORS reminds me of the public health intervention of washing hands before surgeries to prevent infections. In 1846, Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis found that doctors were transmitting infections to women in maternity wards by examining them after doing autopsies and washing hands could prevent this.17 However, medical professionals derided him and his findings. While others echoed his claims, most notably Florence Nightingale,18 handwashing to prevent infections became common only decades later.

In certain contexts, underwhelming perceptions of ORS have filtered down to patients, who might prefer other treatments over it.19

The scholar Rachel Hill-Clifford talks about how larger health equity and access issues can affect certain treatments. Citing the limited accessibility of healthcare in Guatemala, she writes: “If families do pay and take the time to travel to a healthcare facility, they want to be compensated for their efforts with a treatment perceived as strong and effective. ORT is not perceived as such a treatment”.20

In public health interventions, we need to embrace and evangelize the idea that in certain cases, less is more.21 Healthcare providers overprescribe certain treatments, such as antibiotics,22 where simpler ones would suffice.

But merely providing a simple solution or sharing knowledge regarding it is not enough. We also need to address deep-rooted motivations and beliefs. These might seem irrational, but often have a logic to them.

However, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.24 What may have worked in one location might be unsuitable for another. When implementing strategies to increase ORS use — or for that matter, any public health intervention — it is important to consider the local context and social determinants of health.23

In certain contexts, the solution could be deceptively simple. The Science study’s authors mention that since patients nudging doctors increased ORS prescriptions, just putting up a poster telling patients to ask for ORS rather than, say, antibiotics could be a way forward. Providers too thought it would give them more credibility when they prescribe “something as simple and basic as a pack of salts”.13

Occam and his razor26 would agree — sometimes, the simplest solution can be the best one. The first step would be to acknowledge it.

*ORT (Oral Rehydration Therapy) refers to the proper use of ORS, but both terms are often used interchangeably.

Some of the visuals used in this blog are AI-generated on Canva.

The mission of the Boston Congress of Public Health Thought Leadership for Public Health Fellowship (BCPH Fellowship) seeks to:

It is guided by an overall vision to provide a platform, training, and support network for the next generation of public health thought leaders and public scholars to explore and grow their voice.