Photo by Dotun Sangoleye on Unsplash

Mariama, a Soussou1 woman living in Guinea, West Africa, had a hard life growing up. Her parents divorced when she was young, and after enduring abuse from her mother, she was moved to her maternal grandmother’s home. When her grandmother moved away, following her son to a new village where he was promoted, Mariama was expected to stay behind to continue school and was moved to the home of her grandfather’s second wife. (Polygamy, the practice of having more than one spouse, is common in Guinea, where 43% of married women were in a polygamous household in 2018.2) For Mariama to attend school, which she did on and off through Year 6, she often had to seek bread and coffee from neighbors, as food was difficult to find.

“She did not take care of me,” Mariama reflected. “Since my grandmother left, I was in this suffering.”

Mariama was forced into marriage around age 13, though she could not remember the exact date. Her parents, especially her father, had become disturbed by information they received from family members about Mariama’s daily routine; she attended school followed by a youth dance hall with her friends, and she believes that is what led to her marriage. Her mother was a vendor at Madina Market, one of the largest markets in Conkary, the capital city, when another vendor spotted Mariama. She told Mariama’s mother that she was seeking a young wife for her younger brother and that her brother was diamond merchant.

“My mom was deeply moved,” she recalled. “I said that I did not want this man, but the man insisted that he wanted me. The wedding was celebrated without him. They celebrated my marriage. Then, they sent me here [to Conakry] accompanied by one of my aunts.”

Mariama’s wedding was a disheartening affair. “I had just left school. I told [my friend] that I was tired. I was sleepy. [My family] came to find me. I was sleeping. They woke me up. They took me. I refused to go. They tied me up and made me go inside the taxi. They made me get married.” Though she pleaded with the local chief’s wife to appeal to the chief and prevent the marriage, saying that she did not love the man and that she did not want to stop attending school, the wedding was celebrated. She was married in religious tradition, and not civil law, because Mariama refused to sign the paperwork.

While Mariama described that marriage is for “love” and “eternity,” she was unable to share positive experiences of what she endured in the four years she stayed with her husband. She was frequently beaten and verbally abused and remembers her husband threatening her because she made him waste his money on a loveless marriage. She still wears glasses to correct failing vision in her left eye from one of his violent attacks. She described him as a tyrant, a “dictator,” who treated her as a maid rather than a cherished partner.

Mariama’s story is not unique.

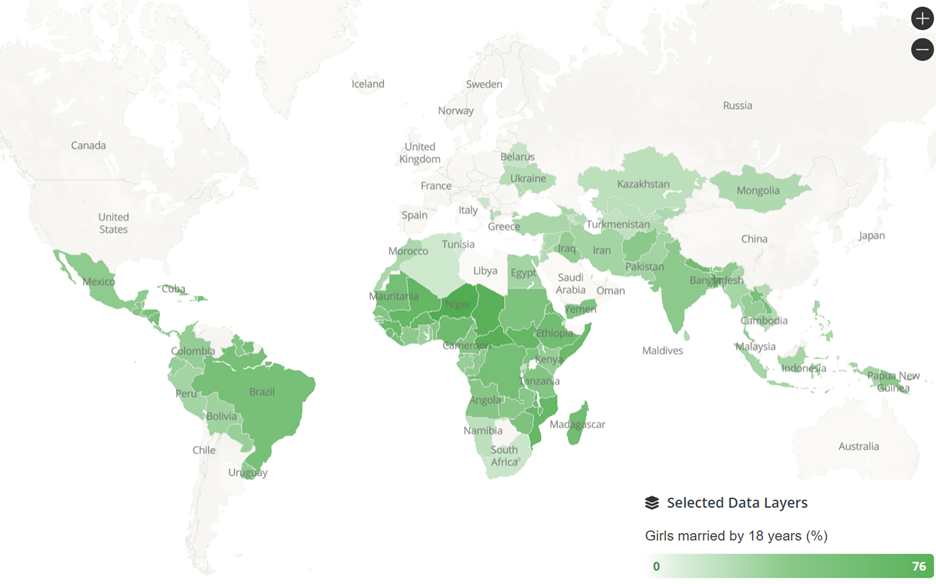

Girl child marriage, defined as a formal or informal union of the girl-child before age 18, is a practice that happens all over the world3. In Guinea, a French-speaking West African country of 13.6 million people, 1 in 2 girls marry before their 18th birthday4. This high percentage might be surprising, as the marriage of a girl-child before age 18 was deemed illegal in Guinea’s 2008 Children’s Code. But it’s not just Guinea where this practice, and similar stories, occur. It’s estimated that 650 million girls and women, compared to 115 million boys and men, have married as children.5 Rates are highest across sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, and no region is on-track to eliminate the practice by 2030, as committed to in the Sustainable Development Goals. 6

Image © Girls Not Brides 2023

During my time in Conakry, Guinea, conducting interviews and participating in the lives of women like Mariama, what struck me most were the challenges that surrounded the fraught, and often undesired, early marriages. Women like Mariama described negative health consequences, including poor sexual and reproductive health, intimate partner violence, poor mental health, and even poor physical health, such as a consequence of violence in the relationship.7 These health consequences have been documented in Guinea and elsewhere, amplifying the potential harm that the circumstances surrounding an early marriage can have.8,9,10,11,

There are global efforts to bring an end to child marriage. Girls Not Brides, a global partnership, connects organizations across the world all working toward a common cause.12 Its sister organization, the Girls First Fund, raises money and delivers resources to community-based organizations working in countries like Guinea to bring an end to child marriage and advance gender equality.13 UNICEF, the United Nations agency focused on children, and UNFPA, the United Nations agency focused on sexual and reproductive health, partner to advance the Joint Programme to End Child Marriage, which advances the rights of girls through at-scale programming across 12 countries.14 These organizations, just a handful of those I got to work with during my time as Advisor, Gender-Based Violence and Child Marriage at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation15, are important examples that remind us of the power of working with community and centering gender equality to improve health.

Although Mariama’s story continues, it, sadly, doesn’t have the happiest of endings. But she did ask that in my research, I use my authority “to help us save girls from marrying at an early age.” While I may not have such authority in Guinea or any other country, I do have a platform to share her story and a commitment to advocate to improve the lives of Mariama and other girls.

And that’s what sharing this story is intended to do: to remind us that we cannot unlock progress in health without truly listening to and honoring the experiences of women and girls.

This interview was conducted, with consent, as part of a wider research study titled “Mariage et Bien-être en Guinée: Une Etude Qualitative” / “Marriage and Well-Being in Guinea: A Qualitative Study” (PrincipIe Investigator: Yvette Efevbera). This research was approved by the Government of Guinea, the Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (108/CNRES/16), and the Harvard Longwood Institutional Review Board (IRB16-0939). Results of the broader study have been published elsewhere. Mariama’s name was changed to preserve her identity. The author is grateful to Mariama, research advisor the late Dr. Paul Farmer, and the countless individuals who were formally and informally part of the team that made this research a reality.

UNICEF, 2022. “Towards Ending Child Marriage: Global Trends and Profiles of Progress.”

The mission of the Boston Congress of Public Health Thought Leadership for Public Health Fellowship (BCPH Fellowship) seeks to:

It is guided by an overall vision to provide a platform, training, and support network for the next generation of public health thought leaders and public scholars to explore and grow their voice.