A priori: Assuming a logical outcome without actually observing it to be true (1)

A priori: Assuming a logical outcome without actually observing it to be true (1)

The critique a priori is commonly applied in medical literature. While a priori assumptions facilitate hypotheses and potentially solve problems in healthcare, they also risk ignoring or directly harming patients caught in a hypothesis’ blindspot.

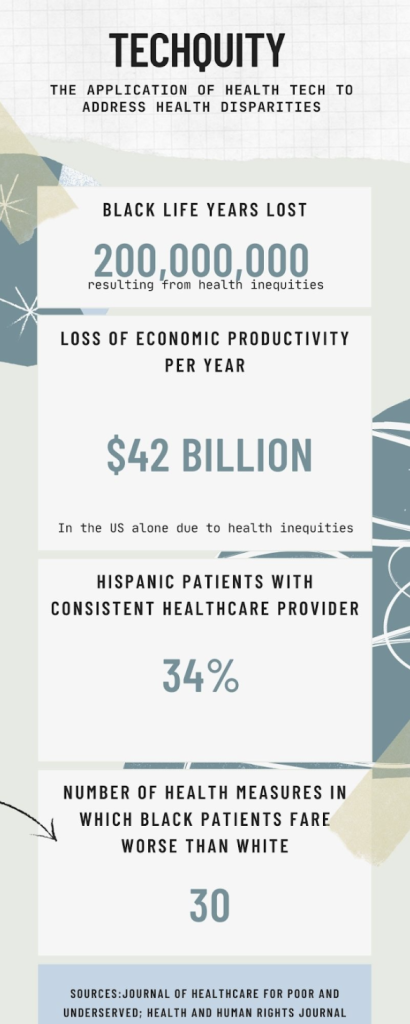

Techquity has become the a priori underpinning of the health tech industry. It refers to the idea that healthcare tech is a driver of equitable care when designed appropriately (2). The COVID-19 pandemic amplified racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities across the globe with people identifying as black, indigenous, and people of color dying at disproportionately high rates (3). In the US alone, health inequities contribute to the loss of over 200 million black life years due to lower life expectancy (4). Additionally, inequities contribute to a $42 billion loss in economic productivity per year (4). The Covid-19 pandemic drove demand for remote care combined with both the ethical and economic indictments of structural racism provided ample opportunity for health tech to market itself on the basis of health equity.

From telemedicine/healthcare analytics targeting marginalized medicaid recipients to AI-supported platforms gamifying healthcare access for hard to reach populations, there is no shortage of tech arguing its place in the fight for health equity (5,6). However, there is a simplicity and optimism to the health tech gambit that obscures the risks and potential exacerbation of injustice health startups may inadvertently impose.These risks come in two broad forms: the nature of venture capital itself and the dangers of big data.

Image 1: Summary of Techquity and health inequities it may arguably address (2,3,4)

Health startups are built on the premise that good healthcare and good business are synonymous. Yet, good business means increased profit for investors or shareholders and requires funding dependent on the market whims (7,8). The very market that underwrites venture capital funding of startups also shapes the social inequalities that drive health disparities. Take for example the Great Recession of 2008, driven by housing speculation and reckless mortgage financing (9). Analyses of health outcomes resulting from the crisis noted globally worse morbidity, mortality, and mental health measures with low income and minority communities suffering the most (10,11). While a recession may be the most acute and obvious example, the disparities created in order to amass capital are globally repeated and insidious (11).

Some argue that with a committed mission, health startups provide counterbalance to the inequities of the current world economic system. However, from 2021-2022, the total value of digital health startups shrunk to $21 billion from a peak valuation of $30 billion (12,13). This contraction is driven by the gap between the measures of success in the startups and those in healthcare. Startups advance by fundraising and valuation accomplished on a relatively finite timeline. Financial benefit for venture capitalists is most significant when a startup is acquired by another company or made available for public trading. Conversely, health outcomes are nuanced and incremental, occurring on a scale beyond the patience of investors (14). Thus, innovation and reach for ambitious health outcomes are compromised by investors seeking their returns.

All health tech companies rely on some form of collecting and interpreting data and using it to improve outcomes and access to care. Yet, even the most seemingly objective data has the potential for significant bias. This is especially true with the rising use of artificial intelligence (AI) in health tech (15).

While startups have collected massive repositories of health and personal data, AI relies on the algorithms we feed it to interpret and utilize that data, exposing them to the implicit bias and racism that already pervades our health systems (16). For example, an AI designed to assist physicians with assessment and plans was more likely to label physically agitated African American patients as violent compared to white patients and even recommended police involvement or jail (17,18).

While startups often argue that better data collection mitigates such bias, this fails to recognize the historic weight and insidious nature of assumptions used to build treatment algorithms. Case in point, much of our knowledge base regarding risk management of cardiovascular disease is based on The Framingham Heart Study. Although it was one of the largest and longest studies of cardiovascular risk factors, its sample consisted of an 80% white population, performing poorly in assessing risk for African American patients(19). Consequently, efforts to only examine present data collection without considering historical data inequities risks continuing to amplify health injustice.

Just as concerning as the misinterpretation of data is the potential theft of data. In 2021 alone, 45 million patients had their protected health information accessed inappropriately and the Washington Post recently reported on an incident in which identifiable health data used in training AI was temporarily accessible to the public via Google search (20, 21). Exposure of personal data not only violates a patient’s right to privacy, but could incur a significant financial burden, further widening both financial and health inequities.

Health inequities are the result of centuries of injustices and deliberate exclusion of communities across the globe. The unequal distribution of capital and hyperaccumulation of wealth suggests that inequality may be an inherent characteristic of capitalism itself. It’s clear that our current healthcare practices are failing to meet the World Health Organization’s stated goals for health equity, and the excitement and rapid innovation of health tech offers hope in a stagnant present of healthcare delivery (22). While we must take pragmatic steps to further health equity, doing so necessitates a clear-eyed reckoning with the weight of history. This is not a call to reject health tech or the benefits reaped from startup innovation. Rather, it is a call to embrace innovation with an understanding of the economic and social forces that have afforded us this moment. It is imperative to regulate the industry to prioritize patients over profits and advocate the adoption of privacy protection and historically competent data collection (23).

The mission of the Boston Congress of Public Health Thought Leadership for Public Health Fellowship (BCPH Fellowship) seeks to:

It is guided by an overall vision to provide a platform, training, and support network for the next generation of public health thought leaders and public scholars to explore and grow their voice.